Writing

Novels • Children’s Books

Back to Anne’s Home Page

Write, don't talk. A blank page listens.

I write both fiction and nonfiction. There's a certain overlap. I try to weed personal and subjective stuff from my nonfiction. With fiction, I stick to the truth.

I've helped write building codes and technical works on historic preservation. That was a lot better than silence, but it wasn't as good as inventing my own world, so I wrote a novel. And another. And finally, animal stories for children and imaginative grown-ups as well.

This is my page for the novels and children's books. Just scroll down, or use the quick links below to jump to a certain title. For nonfiction, see my pages for soapmaking, cookie molds, housekeeping, and living apart together.

Novels

Skeeter ~ Pacific Avenue ~ Joy ~ Flight ~ A Chambered Nautilus ~ Cassie’s Castaways ~ Willow’s Crystal ~ Benecia’s Mirror ~ Departure

Children’s Books

The Mice Before Christmas ~ Katie Mouse and the Perfect Wedding ~ Katie Mouse and the Christmas Door ~ The Secret of Gingerbread Village ~ On Christmas Eve ~ If Wishes Were Fishes

Novels

Skeeter

“If cats wore bumper stickers, Skeeter’s would read ‘Question Authority.’ He’s everywhere, expressing his opinions, giving and demanding affection, and bending the rules. More than once, I’ve decided there must be two of him.”

When a stray kitten romps into Lynne’s life, she has no idea what she’s getting into. As Lynne describes in letters to her friend Angie, Skeeter is all cat—high-spirited, contrary, and inventive. He’s so goofy that he reminds Lynne of her own nuttiest escapades; so irrepressible that even Lynne’s neighbor, Mark, gets wound around his paw.

Angie pays Lynne a visit to see Skeeter for herself, and the story reaches its comic finale. No one who meets Skeeter will ever be quite the same again.

Skeeter never does anything without a reason. There may not be much point, but there always is a reason, if only I can find it.

I’m still puzzling over his nighttime antics, though. I wish I could ask him what he thinks he’s doing.

I go to bed early. Skeeter does not. This is normal, since cats are more or less nocturnal. My bedtime coincides with his high-energy evening play session, so I shut him out of the bedroom.

However, I usually wake in the middle of the night. As I wander down the hall to the bathroom, Skeeter sneaks into my bed.

When I return, he snuggles and purrs, the ideal cat. This is to fool me into letting him stay. Once he manages that, a demon gets hold of him. He jumps into the open window and yowls, then thunders back across my prone body to my desk, where he chews pencils and shreds all the paper he can get his paws on. Then he attacks the wind chime and the sewing basket. He sharpens his claws on the bed skirt, turns over the wastebasket, and raids my jewelry box.

At this point, I eject him from the bedroom and shut the door. He doesn’t like this. It’s a good thing he can’t talk.

Pacific Avenue

Even though I enjoyed my comic stint, my next novel, Pacific Avenue, turned out to be serious. It's a story about young people in the early 1970s, the time of the war in Vietnam. It isn't the story of anyone I knew. The places are real, though—New Orleans and San Pedro, California, both places I've lived in and loved.

Here's the beginning of the first chapter:

I chose a window seat on the Greyhound, but I didn’t look out. For almost the whole trip, I stared at the rough tan upholstery of the seat in front of me. It had a rip on one side and three dark stains.

A woman settled into the aisle seat. She raised her footrest, but it clunked back down. When I glanced her way, she caught my eye and smiled.

“How do you make these things stay put?” she asked.

I meant to answer—the words were lined up in my mind. But before I could say them, they slipped apart like beads when the string breaks. I gave up and studied the seat cover again. Still tan, still ripped, still stained. The next time I looked, the woman was gone.

Evening came, but I didn’t use my reading light. Late at night, awake in the breathing dark, I imagined running my fingers over the seat back, erasing the stains, mending the seam. In the morning, I almost believed I could fix it. So I took care not to touch it, not to find out for sure.

In the afternoon, the bus left the freeway and crept through downtown traffic. I turned then, and peered through the mud-spattered window. As far as I could see, Los Angeles was a city of warehouses. I sank back into my seat.

When we reached the station, I claimed my suitcase and dragged it through the waiting room to the street. Outside I found blank walls and empty sidewalks. No direction and no one to ask.

Well, I ran away from college, then from New Orleans, and then Baton Rouge. Is it too soon to run away from here?

The traffic light at the end of the block turned green, and cars passed me by. When a city bus stopped and opened its doors, I climbed on. I couldn’t think what else to do.

I paid the fare out of my change purse and took a seat near the front. Even though I pulled my suitcase aside, it poked out into the aisle. More people piled on at every stop, and all of them had to squeeze past it. I expected everyone to glare, but nobody gave me a second glance.

The bus started, stopped, started again. We passed through neighborhoods with trees and shops. The crowd thinned as passengers got off, going home. Should I get off too? No, not here. Where? Next stop, no, the one after. No, not that one. Every stop would be a whole different life, a different second chance.

Choose, choose. I couldn’t. I rode till the bus pulled over and parked.

“Seventh and Pacific, San Pedro, Port of Los Angeles,” called the bus driver. He turned to me and added, “End of the line, Miss.”

Joy

I've always loved carousels, and restoring old things, and Northern California. So my third novel is about a carousel restorer in Oakland and San Francisco. It's a more upbeat story than Pacific Avenue—though some very strange things happen, most of them are a generation in the past, revealed through old letters and the musings of a woman who hasn't forgotten. In the present is a love story, and the story of bringing an antique carousel—and a young woman's hopes—back to their former beauty and harmony.

I hurried the few blocks to the park. Using the keys my client had sent me, I slipped in quickly through a side gate and locked it again behind me.

The carousel was at the edge of the park in a shabby barnlike building. When the carousel opened, the big doors on every side would roll up and disappear. The shadows inside would heighten the glitter of lights and whirling mirrors. But now the building was abandoned. I unlocked a small door and stepped into blind dark.

I’d studied everything I could find about this carousel. It had all its original animals. Like many carousels of the early twentieth century, it was a menagerie—it included everything from a goat to a sea monster. There were two chariots, designed for ladies’ modesty. . . . In my mind, 1906 blossomed again. I could see the ladies in their Edwardian dresses, their hair piled high. Beside the band organ, Charles Looff, the carousel’s maker, stood glowering at me, stocky and mustachioed. I could read his mind: Who is this tramp woman in blue canvas trousers?

“Times have changed,” I told him. “It’s okay. I’m here to fix it. Remember me? I worked on the one in Silver Spring. Tell your guys, would you? Tell them to give us a hand.”

My voice rang hollow in the closed-up building. I turned on the lights and blinked at the mess. Far, far worse than I’d been led to believe. I’d expected park paint, but not in every color of the rainbow. Pink, purple, chartreuse . . . . Dear God, had the painters been drunk? Even the jewels in the harnesses were buried in paint. The horses, originally fitted with real hair tails, had nothing left on their rears but obscene-looking sockets. As I stepped onto the carousel, part of the floor felt shaky and rotten.

I walked among the animals, touching their faces, knowing how they’d look when I was finished. The horses would be dapple gray, palomino, bay, and roan, like real ones, with new horsehair tails. Looking through the dirt with a restorer’s vision, I saw bright new paint, the trappings and harnesses gilded and shaded. I could make them special again, the pride of Peregrine Falls.

Whenever I’d coaxed a carousel back to life, the town would have a party to celebrate. Dignitaries would speak, usually at length. Everyone who’d helped the project along would be recognized and applauded. Finally, I’d be asked for a few words.

“A few words” was exactly what they got. I’d tell them I hoped they’d enjoy the carousel, and invite them to get in line behind me to buy a ticket for the first ride.

I’d mount one of the jumpers and the carousel would start. A moment of pure triumph, and it wasn’t the newspapers and the speeches that made it that, it was the swooping animals and the gongs, the colors and lights. With a little luck, the band organ might even be tinkling my favorite carousel tune:

After the ball is over,

After the break of morn,

After the dancers’ leaving,

After the stars are gone . . . .

Flight

Linda is seventeen years old. She has OK parents, a bratty little brother, an almost-boyfriend...and then her life gets turned upside-down. Flight is the story of how she makes it right again, and who she becomes by doing that.

Some of Olympia’s alleys aren’t even paved. Just parallel tire tracks drifting through ruts and puddles, crowded by a patchwork line of back fences. I love those alleys, with their overhanging apple branches and tangles of blackberry canes. They’re like country roads stitched through the city. I walk ten alley miles for every one on the sidewalk, basking in the sense of peace. I laugh at the acrobatic squirrels and feed my curiosity with glimpses of the candid backs of houses. The alleys are part of my home.

Besides, someone might see me if I walk along the street.

So, I avoid the sidewalks as much as I can. It’s easy, since my front door is just off one of those shady alleys. And most of the places where I work are old houses, with gates in their backyards.

Some of my clients don’t get it. The second week I worked for Mrs. Clemens, she tried to set me straight.

“You don’t have to come to the back door, Lainie,” she said. “I never did hold with making the girl come to the back door.”

I stifled a laugh. Back in my other life, “girl” was a word Mom taught me not to let people use about me. But what she had in mind—what her whole generation had in mind, as far as I could tell—was men referring that way to women in general. While to Mrs. Clemens, “the girl” was a female servant. It would never have occurred to Mom I could be a “girl” in that sense.

Anyway, I didn’t mind. I liked Mrs. Clemens, and I was happy to have the job. Ninety-one was too old to learn to mince words.

“Thanks,” I told her. “I wasn’t thinking you expected me to come to the back door. But it’s a shortcut from my place. And I like to see what needs doing in the yard.”

She gave me a shrewd look as I served her breakfast—half a pink grapefruit and two pieces of raisin toast. An old teacher is hard to fool. Back in San Diego, I lied all the time at school, just for the fun of it. Those teachers probably didn’t believe me either, but I was too wrapped up in myself to see it. Now everything about me is a lie. My name isn’t even Lainie.

It isn’t fun anymore. But there’s no way to stop.

A Chambered Nautilus

Nita walked away from her family when she was seventeen years old, determined to never look back. But forty years later, when her mother died and her father descended into Alzheimer's, Nita returned to New Orleans to care for him in his final months.

Now her father has passed on, leaving Nita her childhood home as an inheritance. But she soon finds she isn't the only resident. The house is occupied by ghosts of her past, playing out scenes of the life she fled.

What are they trying to tell her? Will they ever leave her in peace? And are they really spirits, or only visions, emerging from sealed-off depths of memory as from the shell of a chambered nautilus?

Next were photos and negatives. For a while, Dad had a good camera, and he developed black-and-white negatives and prints at night in the bathroom. The camera was gone—probably he'd sold it at some point, when he needed money to pay creditors who couldn't be stiffed.

The pictures were beautiful. He'd been talented, and had tried to go professional. But his photography business had failed just like every other one before it. Now, I looked with bewilderment at portraits of us as children. Somehow, he'd lost the love that shone from them, packed it away in a cardboard box, forgotten as old bank statements and unpaid bills.

I kept coming back to one set of photos of Manda, Lou, and me on Christmas morning. Sitting near the tree, opening our presents. Our smiles and shining eyes were captured forever. But Dad was gone, and the love that inspired those photos had died long before he did. How had he turned into a man who threw Christmas in the dump, every last elf and star, every last shred of tinsel?

I pushed the box of photos aside.

With two more empty boxes, I sorted for any records that had to do with Dad's last business venture, the successful one. After I'd left home, he'd invented several toys that caught on and made enormous amounts of money. Manda had told me about it at the time, but I'd dismissed it as ironic: How could a man who disliked children have invented amazing toys?

Now I remembered he had made that rocking horse. And bunny shadows on the wall, and a herd of charming animals he sculpted for us out of multicolored telephone wire. I remembered more and more. He hadn't started as a man who disliked children.

And Mom. When had she changed from the cake baker, the most beautiful woman in the world, to the one who screamed that she wished we didn't exist?

I remembered what the ghosts had shown me, and more. The miscarriage. The finally fulfilled longing for a son, followed by gut-level battles about what a son should be. Years of failure and scarcity, dinners of scraps, our filthy house, neighbors who shunned us. Anger feeding accusation in a vicious circle.

Beyond that, the truth was as tantalizing as a mirage. Why did their marriage go bad? Which of them had started it? Trying to figure that one out was like watching a tennis match. She did this because he said that, because she said that, because he did this . . . back and forth, back and forth . . .

I grinned suddenly, remembering Lou's description of tennis—"the kind of thing a cat would watch."

It was unsolvable. Whatever had gone wrong between Mom and Dad had gone disastrously wrong. War had been declared, and as in all wars, there was "collateral damage." Which was military-speak for what happens to innocent bystanders. Like kids.

Cassie’s Castaways

(Island Women Trilogy #1)

When Amy Bendbowe receives a call for help from her dying mother, Cassie, she rushes from Washington's San Juan Island to Mobile, Alabama, to see her. But Cassie has other ideas. Before letting Amy visit the hospital, she wants her to sell off or give away all the stock from Cassie's secondhand store. Is Cassie trying to keep the distance that has long separated her from her daughter? Or is this her way to help Amy finally understand her?

When I looked up from the book, I saw it was dark outside. Time to pay a visit to Lauren’s moon garden.

It was a good night for it. The moon was nearly full, and it outshone the weak streetlight at the end of the block like a light bulb against a candle. Lauren’s fence, dark in sunlight, was silver-washed. The gate creaked loudly as I opened it, and I saw a curtain flicker. I stood still, wondering if I should knock and say hello, but decided there was no need to.

A breeze rustled leaves, and a sultry perfume filled the air. I traced it to a bush with hanging white flowers like tassels. And farther on, another scent—white flowers climbing a trellis. Others close to the ground, and a shrub that smelled like apricots. Everything glistening, fragrant, white, ethereal.

I picked out the shape of a bench in a corner, and sat to take it all in. Tiny lights flickered here and there, and I realized I was seeing fireflies for the first time.

I imagined Cassie sitting beside me, thought of all the things I’d like to ask her. But I’d get no more answers from her than from the moonlight on the garden. Or if I did, I’d understand no better than I understood the far-off song of what I guessed must be a mockingbird: a phrase it repeated, elaborated, then discarded for another.

The bird went on and on, as if trying to tell me something in a hundred different ways. I stood, suddenly tired and stiff. I went back to Cassie’s run-down house, dropped my clothes on the floor, and fell into bed.

I dreamed I was home, sitting on the beach, with driftwood logs around me, white in the moonlight. I looked out across the bay toward a little island, and saw a dark line like a path along the surface of the water. I heard footsteps, and David’s voice behind me.

“Let’s go home, Amy,” he said. “It’s getting late.”

I woke with the smell of the cool sea dissolving into the reality of Cassie’s stuffy bedroom. I could no longer hear the mockingbird, but the chirping of other birds told me it was dawn.

Let’s go home. It’s getting late.

Willow’s Crystal

(Island Women Trilogy #2)

Rai Ireland has built a respectable life for herself as a novice real-estate lawyer on Washington's San Juan Island. But when her hippie mother, Willow, comes to stay with her, Rai finds herself stretched between the Rachel she calls herself now and the Rainbow her mother thinks her to be. Besides, it hardly seems fair that Willow adjusts so easily to island life, while Rai still navigates the narrow straits of dating on a small island.

The island changed all the ideas I’d had before I saw it. It was nearly crime-free, gorgeous, and—mostly—welcoming, but the lack of choice could be maddening. Mom and I had lived in smallish towns before, and I’d thought I was prepared, but the island was so isolated, it was a whole different story. You ate what the grocery store had, unless you wanted to go to the mainland and fetch something else. If none of the stores had your favorite brand of shoes or shampoo, you figured out what else would do. And probably paid more for it, even if it wasn’t as good.

If you didn’t like any of the mechanics in town, or any of the doctors, you had to decide which one you disliked the least. On the up side, most business people really were nice, and more than honest. The prices were sort of eye-popping until you realized that everything had to be brought in by boat, and all the trash had to be hauled somewhere else. It was a logistic work of art that the place was there at all.

Even more than the problems of life on an island, though, I had personal complications. In college, I’d been too busy to even think about men—I’d either been studying or working, in a frenzied rush to get myself out of the poverty that Mom accepted so easily. Now I had time to date, and I knew a lot about what I wanted—and nothing about how to get it. For a twenty-five year old, I was seriously behind the curve.

I didn’t care about guys’ age or looks, at least within really wide bounds. I’d had ringside seats for a couple of awful relationships that girlfriends had had with sexy, “dangerous” men. As far as I was concerned, if a guy looked like the latest hot movie star, that was two strikes against him right there.

What I did want was someone who was looking for a serious girlfriend, a partner. Maybe even a wife. If that was uncool—and I’d known plenty of people who thought it was—too bad. I wasn’t lying to myself—I wanted to meet a good guy and stay with him. The trick was to find a man who was looking for the other half of that equation.

Several men had asked me out from time to time, nothing serious. I guessed it was a sort of “new girl in town” thing—probably the choice in the dating world wasn’t a lot more extensive than what you got in the supermarket, to put it a bit crudely. I was taking it easy, not getting too close to anyone until I was sure it wasn’t just novelty they were after. And of course, in a small town, everyone knew what everyone else did, pretty much. It wasn’t like I could date here and there without everyone being in the picture.

Mom could easily throw a monkey wrench into the works, especially if she lived with me. It was dicey enough to be tiptoeing around “yes, no, maybe so” with the island men, but having a San Francisco wild woman mother underfoot was definitely going to make things interesting.

Benecia’s Mirror

(Island Women Trilogy #3)

Susan Jarvin could hardly be more surprised when her elegant musician mother, Benecia, accepts her invitation to visit Washington's San Juan Island. But more surprises are in store, as Benecia shows a new, strong interest in Susan's young son, and then starts dating his diving instructor, a man more than a decade her junior. It's all a bit much to cope with, on top of dealing with an ex-husband that Susan never quite stopped loving.

When my father died—it was early summer in 1998—his fortune was divided among the family. Also, his lawyer sent a letter by registered mail. I assumed we all got one, but I didn’t ask

He laid out what he knew about all of us. The family was big, and he had lots of beans to spill. For instance, that his sister, who’d been her church’s treasurer, had “retired” because she’d embezzled from church accounts. She hadn’t been prosecuted because Dad had repaid them, plus a big contribution. Her husband had seduced their underage babysitter. Dad had bought the parents off.

He and my mother had been divorced a long time, and he provided a great recap of the messy details—courtesy of a private detective he’d hired—of her supposed wild life in L.A. in later years.

There was more, a lot more. A cousin’s psychiatric hospitalization. A bankrupt shopaholic. A couple of DUIs. A flasher. A niece’s abortion. Every sin in the book, and several more crimes.

If anyone was spared, I couldn’t think who. Skeletons fell out of the closet like a load of bricks off a dump truck. It was a reenactment of Pandora’s box—or maybe bad daytime TV. He twisted the knife by declaring that anyone could claim innocence by refusing his money. No one did.

Departure

When Henry “wakes up,” he finds himself walking along an empty stretch of road on modern-day San Juan Island. He doesn’t remember much about himself, besides his name and the fact that he’s dead. How did he die? How long ago? What was his life? Did he have a family? Why is he still on the island? And most important, what is a ghost like him supposed to do now?

On Henry’s journey of discovery, he meets another ghost in the same predicament—a little girl named Charlotte. Together they navigate the byways of the island and of their own memories, in search of the keys that will finally free them for departure.

Part ghost story, part historical novel, part fable, Anne L. Watson’s latest weaves island lore, human insight, and spiritual wisdom into a magical tale of redemption and fulfillment.

When I woke up, or came to, or whatever it was, I was walking south on Roche Harbor Road. Southward, anyway. That road turns and curves, and at any moment, you might be walking east or west, even if you are headed south in the end. That’s the way San Juan Island is—a lot of hills, and the roads wind and twist. It’s easy to end up in places you hadn’t planned to go.

I didn’t know how I knew all this, or how I knew my name was Henry, and that I was a middle-aged man—not a very good man or a very bad one. Or that I’d belonged here on the island when I was alive.

Or that I was dead.

It might have been a strange thing, knowing I was dead, but it wasn’t any stranger than when I was alive and knew it. Just another fact.

What I didn’t remember right away was when I’d lived, or whether I’d had a family, or why I died—most of the things you might think are important.

So I was a ghost with a lot to learn.

I checked to see if I was invisible. I should be, I thought. But I could see my own hand—it was muscular and callused. And scarred. An ugly hand, one that had worked hard and never been treated well.

But after a minute, I realized that seeing myself didn’t prove much. I could still be invisible to living people.

Next thing I noticed was my clothes—a blue work shirt and denim overalls. Everything was clean, and the shirt was ironed, but I could tell it was old because the cuffs were fraying.

I had good strong boots on my feet, but one of the laces was almost worn through. I frowned. Not sure if it would break, or if I could get new ones if it did. I wished I’d kept up my clothes better when I was alive, but maybe I didn’t have the money. That made sense to me: No, I had not had much money.

I was making progress, I thought. Getting some idea who I’d been. Poor. That’s who I’d been.

The road surface was hard—much more solid than the old mud trough that Roche Harbor Road used to be. I wondered what they’d done to it. It looked like it would work pretty well, even in the rain. But it wasn’t easy on my feet.

I walked on, not knowing why. The sun wasn’t quite up yet, but the sky was light and clear, and I could see brown and yellow leaves on maple trees against a background of tall firs. So it was autumn. It looked like it was going to be the kind of day when a man would be glad to be alive. Only, of course, I wasn’t.

Children’s Books

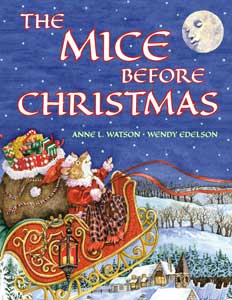

The Mice Before Christmas

“’Twas the night before Christmas,

When all through the house

Not a creature was stirring,

Not even a mouse.”

Everyone knows these lines from Clement Clarke Moore’s classic poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” or “The Night Before Christmas.” But how many know why all those mice were already in bed, or what they were up to before that?

Here at last is a companion poem to reveal all: The holiday hustle and bustle in the mouse house since early that morning. The evening party for all the mouse friends and relations, with presents, feasting, and dancing. And to top it all off, a visit from Santa Mouse himself!

Never before told, this mice-eye story is sure to find a place in your heart beside the original classic.

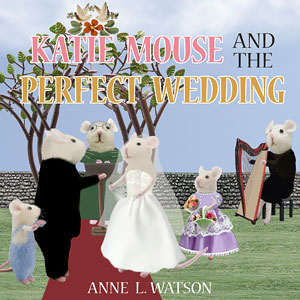

Katie Mouse and the Perfect Wedding

Katie Mouse's Cousin Matilda is getting married! A big wedding has been planned in Mouse Town's public park, and everyone in town is invited. Best of all, Katie will be Matilda's flower mouse, and her little brother Dylan will be the ring bearer.

There's just one problem: The Games Day at Katie's school has been changed to the same day as the wedding! And Katie's the captain of her class's relay race team! Will she really have to miss it?

As Katie struggles with her feelings, a mix-up with the wedding rings threatens to ruin the entire wedding. It's then that Katie discovers that only she knows how to save the day and make the wedding perfect after all.

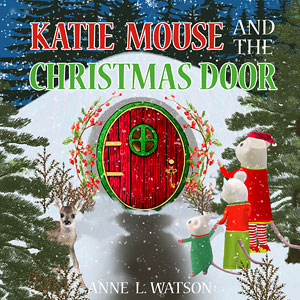

Katie Mouse and the Christmas Door

Christmas is coming for Katie Mouse and the rest of the Mouse family! Papa strings lights on the house and takes Katie and her little brother, Dylan, to get a tree, while Mama puts up decorations and bakes cookies for Santa Mouse. Now, if only Katie could decide what she really wants for Christmas, so she can let Santa Mouse know!

On Christmas Eve, Santa Mouse and his mouse elves arrive to leave gifts for Katie and Dylan. But Alvar, the newest elf on the sleigh, wanders off to explore, and winds up meeting the Mouse children face to face. From the elf, they hear all about the North Pole and the magical Christmas Door, which shows you what you want and need the most.

Can Alvar help Katie discover her deepest Christmas wish? And can Katie help Alvar, when Santa Mouse accidentally leaves him behind?

The Secret of Gingerbread Village

When Coco the mouse slips under a young spruce tree on his morning walk through the forest, he discovers a village of gingerbread houses and "Gingers"—gingerbread men and women brought to life by magic. But all is not well in Gingerbread Village. The Magic that built the village and protects it from outsiders seems to be fading, and the Gingers don't know how to revive it.

Can Coco find a way to help the Gingers? And even if he does, can they trust him enough to let him?

A magical tale of friendship offered, rebuffed, but finally rewarded.

On Christmas Eve

It’s Christmas Eve, and Coco the mouse stands beneath a tall fir tree in the forest. On this night, he tells himself, the forest needs a star for the tree top. If he climbs the tree, he can reach up and fetch one from the sky! But it’s a long climb for a little mouse, and along the way, he’s sure to meet other forest creatures who help or hinder him.

A magical fable of hope, determination, the kindness of strangers, and the wonder of Creation.

If Wishes Were Fishes

There’s an old saying: “If wishes were horses, we’d all get a ride.” But what if wishes were schools of fish? What if they were prides of lions, or pods of dolphins? What kinds of wish could you get from those? Find out in this celebration of animal group names.